-

Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):39.

-

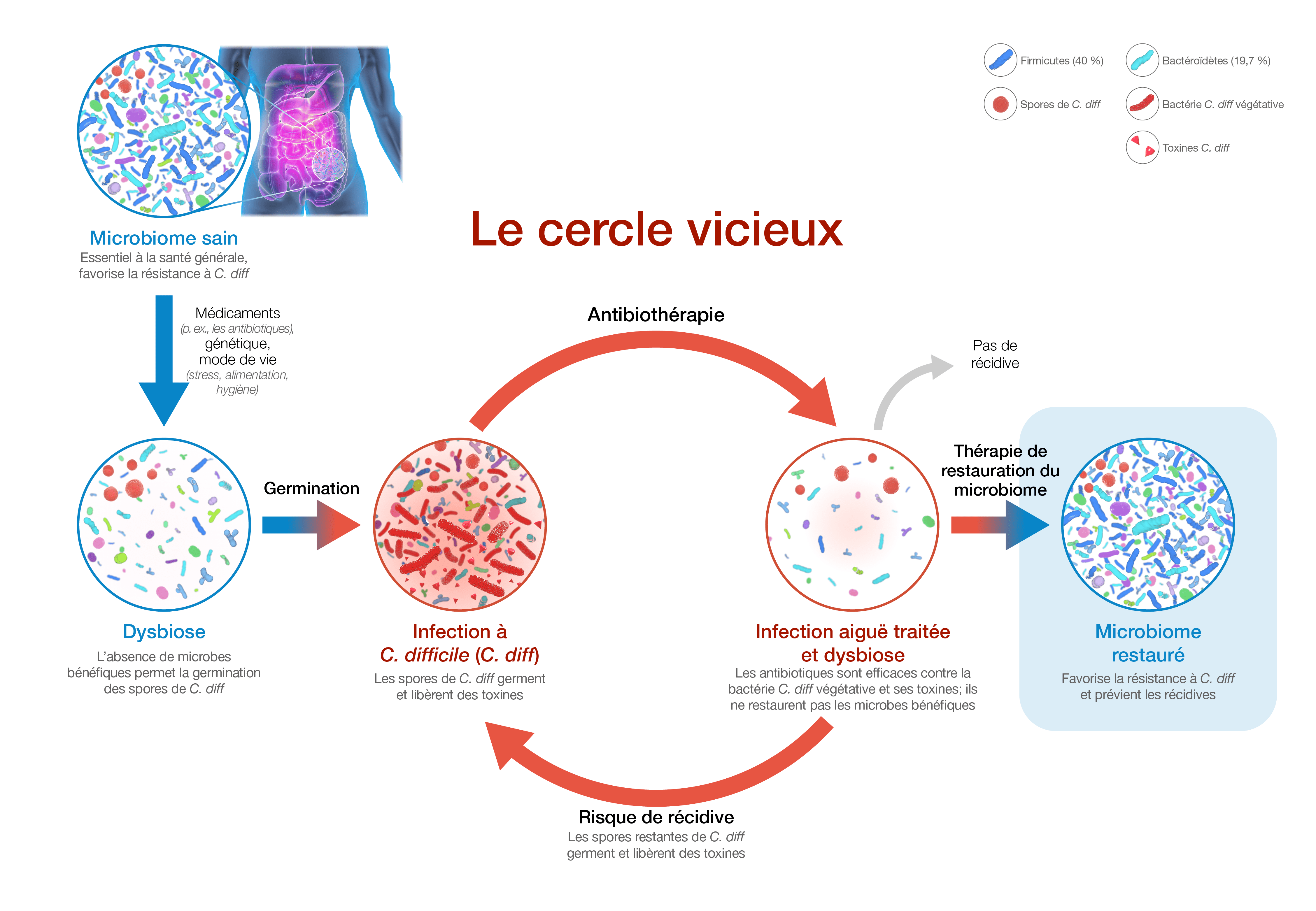

DePestel DD, Aronoff DM. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(5):464-475.

-

Pépin J, Routhier S, Gagnon S, et al. Management and Outcomes of a First Recurrence of Clostridium difficile - Associated Disease in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infec Dis. 2006;42(6):758-764.

-

Leong C, Zelenitsky S. Treatment strategies for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(6):361-368.

-

Kachrimanidou M, Tsintarakis E. Insights into the Role of Human Gut Microbiota in Clostridioides difficile Infection. Microorganisms. 2020;8(2):200.

-

Antharam VC, Li EC, Ishmael A, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis and depletion of butyrogenic bacteria in Clostridium difficile infection and nosocomial diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(9):2884-2892.

-

Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, et al. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med. 2018;24(4):392-400.

-

Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474(11):1823-1836.

-

Wexler AG, Goodman AL. An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2(1):17026.

-

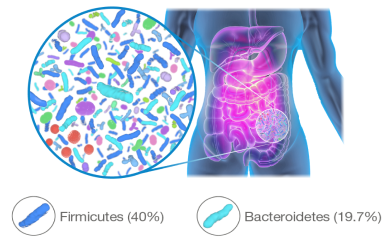

Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, et al. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7(1):14.

-

Nishijima S, Suda W, Oshima K, et al. The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA Res. 2016;23(2):125-133.

-

Faith JJ, Guruge JL, Charbonneau M, et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. 2013;341(6141):1237439.

-

Elahi M, Nakayama-Imaohji H, Hashimoto M, et al. The Human Gut Microbe Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Suppresses Toxin Release from Clostridium difficile by Inhibiting Autolysis. Antibiotics. 2021;10:187.

-

Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731-16736.

-

Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, et al. A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1844-1854.e1.

-

Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63(8):1275-1283.

-

Tremlett H, Fadrosh DW, Faruqi AA, et al. Gut microbiome in early pediatric multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1308-1321.

-

Hevia A, Milani C, López P, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. MBio. 2014;5(5):e01548-14.

-

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, et al. Induction of Colonic Regulatory T Cells by Indigenous Clostridium Species. Science. 2011;331:337–4.

-

Stilling RM, van de Wouw M, Clarke G, et al. The neuropharmacology of butyrate: The bread and butter of the microbiota-gut-brain axis? Neurochem Int. 2016;99:110-132.

-

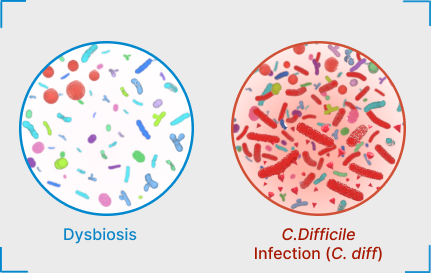

Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):53-68.

-

Kho ZY, Lal SK. The human gut microbiome—a potential controller of wellness and disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1835.

-

Staley C, Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. Contemporary applications of fecal microbiota transplantation to treat intestinal diseases in humans. Arch Med Res. 2017;48(8):766-773.

-

Álvarez J, Real JMF, Guarner F, et al. Gut microbes and health. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;44:519-535.

-

Weiss GA, Hennet T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(16):2959-2977.

-

Riaz Rajoka MS, Shi J, Mehwish HM, et al. Interaction between diet composition and gut microbiota and its impact on gastrointestinal tract health. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2017;6(3):121-130.

-

Knight CL, Surawicz CM. Clostridium difficile infection. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97(4):523-536.

-

Aukes L, Fireman B, Lewis E, et al. A risk score to predict Clostridioides difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(3):ofab052.

-

Ferdyan N, Papazyan R, Walsh D, et al. Rapid restoration of bile acid compositions after treatment with investigational microbiota-based therapeutic RBX2660 for recurrent Clostrioides difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(suppl 1):S15-S16.

-

Theriot CM, Bowman AA, Young VB. Antibiotic-Induced Alterations of the Gut Microbiota Alter Secondary Bile Acid Production and Allow for Clostridium difficile Spore Germination and Outgrowth in the Large Intestine. mSphere. 2016;1(1):e00045-15.

-

Swann JR, Want EJ, Geier FM, et al. Systemic gut microbial modulation of bile acid metabolism in host tissue compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Supp 1):4523-4530.

-

Kelly CP. Can we identify patients at high risk of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(suppl 6):21-27.

-

Smits WK, Lyras D, Lacy DB, et al. Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16020.

-

Wilcox MH, McGovern BH, Hecht GA. The efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: current understanding and gap analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(5):ofaa114.